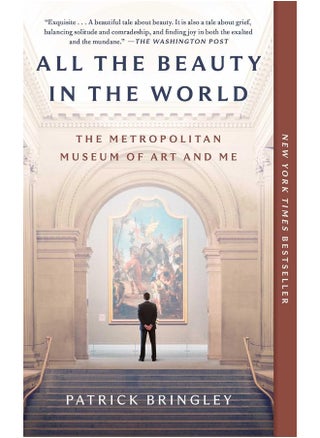

| عن المؤلف | Patrick Bringley worked for ten years as a guard in the galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Prior to that, he worked in the editorial events office at The New Yorker. He lives with his wife and children in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. All the Beauty in the World is his first book. Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved. Chapter I: The Grand Staircase I. THE GRAND STAIRCASE In the basement of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, below the Arms and Armor wing and outside the guards’ Dispatch Office, there are stacks of empty art crates. The crates come in all shapes and sizes; some are big and boxy, others wide and depthless like paintings, but they are uniformly imposing, heavily constructed of pale raw lumber, fit to ship rare treasures or exotic beasts. On the morning of my first day in uniform I stand beside these sturdy, romantic things, wondering what my own role in the museum will feel like. At the moment I am too absorbed by my surroundings to feel like much of anything. A woman arrives to meet me, a guard I am assigned to shadow, called Aada. Tall and straw haired, abrupt in her movements, she looks and acts like an enchanted broom. She greets me with an unfamiliar accent (Finnish?), beats dandruff off the shoulders of my dark blue suit, frowns at its poor fit, and whisks me away down a bare concrete corridor where signs warn: Yield to Art in Transit. A chalice on a dolly glides by. We climb a scuffed staircase to the second floor, passing a motorized scissor lift (for hanging paintings and changing light bulbs, I’m told). Tucked beside one of its wheels is a folded Daily News, a paper coffee cup, and a dog-eared copy of Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha. “Filth,” Aada spits. “Keep personal items in your locker.” She pushes through the crash bar of a nondescript metal door and the colors switch on Wizard of Oz–style as we face El Greco’s phantasmagoric landscape, the View of Toledo. No time to gape. At Aada’s pace, the paintings fly by like the pages of a flip-book, centuries rolling backward and forward, subject matter toggling between the sacred and profane, Spain becoming France becoming Holland becoming Italy. In front of Raphael’s Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, almost eight feet tall, we halt. “This is our first post, the C post,” Aada announces. “Until ten o’clock we will stand here. Then we will stand there. At eleven we will stand on our A post down there. We will wander a bit, we will pace, but this, my friend, is where we are. Then we will get coffee. I suppose that this is your home section, the old master paintings?” I tell her yes, I believe so. “Then you are lucky,” she continues. “You will be posted in other sections too eventually―one day ancient Egypt, the next day Jackson Pollock―but Dispatch will post you here your first few months and after that, oh, sixty percent of your days. When you are here”―she stamps twice―“wood floors, easy on the feet. You might not believe it, my friend, but believe it. A twelve-hour day on wood is like an eight-hour day on marble. An eight-hour day on wood is like nothing. Pfft, your feet will barely hurt.” We appear to be in the High Renaissance galleries. On every wall, imposing paintings hang from skinny copper wires. |

استرجاع مجاني وسهل

أفضل العروض